- Home

- Lou Cameron

Stringer and the Hell-Bound Herd Page 12

Stringer and the Hell-Bound Herd Read online

Page 12

Durler said, “Oh, they’re going on down the Truckee at least as far as Fernley afore they cut east-northeast across the sage and salt of Carson’s Sink. A couple of „em was in here a spell back and I asked „em.”

“Did they tell you how come they’re so anxious to suffer sunstroke in High Summer?” asked Stringer, dryly. He wasn’t expecting an answer but Durler replied, “I asked about that, too. I reckon I’m as curious a cuss as anyone else around here. They told me their outfit is at feud with the Western Pacific. Something to do with the railroad suing „em for freight charges their bookkeeper in Sacramento claims they ain’t entitled to. Makes sense to me, allowing for spite beyond all common sense on the part of anyone ornery enough to hire Chuck Tarington. He’s sort of an ornery bastard as well.”

Stringer allowed he’d met up with the ornery cuss, tried to get Durler to agree to an earlier hearing and, when the town law insisted it wasn’t up to him, cussed some more under his breath and went over to join Willow at her table. She was sipping the cider she’d ordered through a straw. Stringer said he wasn’t thirsty as he explained the situation to the pert brunette. She didn’t seem as upset about it as he was. She said, “Well, I can’t go anywhere until I cash that wired bank draft in the morning, knock wood. After that my plans were sort of uncertain but hardly included a dog day weekend in Dutch Flat! They shut this tiny town down early enough on weeknights. Over the weekend they don’t bother to open up at all. How do you feel about eloping with me to Sacramento or beyond aboard the next train coming down out of Donner Pass?”

He chuckled wryly and said it sounded like fun to elope with her anywhere and when she blushed and said she hadn’t meant it that way he assured her, “Just funning about that part. But the law would surely take it serious if we lit out to leave a coroner’s jury high and dry. You might get away with it, if you migrate to, say, the Royal Bohemian Forest and change your name to Hilda Jane. But everyone knows where I work and I’d as soon spend a boring weekend up here than hunt for a new job in another country.”

She sighed and said, “I’m bored already. That church social they were talking about is likely half over by now, huh?”

He said he felt sure it was entirely over. He was no fool. Neither that pretty Mi wok from the beanery nor the blonde from the general store would ever forgive him, or believe it was platonic, if he showed up with another pretty lady entirely, and a man had to think ahead when he was facing a dry weekend in a strange town.

But that wasn’t the way things wound up, after all. When Willow yawned and allowed they might as well turn in before they got too tired of Dutch Flat to sleep in it, he naturally thought it only proper to escort her upstairs and, it being two flights, she just as naturally had to hang on tight as he did most of the climbing for the both of them. As he unlocked the door for her and handed her the key, she fluttered her lids and murmured, “I’d invite you in for a nightcap if those mean boys hadn’t ridden off with even the pint of horse liniment in my saddle bags. I fear I won’t even have a proper nightgown before I can get to the bank in the morning.”

He smiled crookedly and said, “Nobody’s apt to notice if you turn in Indian Style, the one night. With your permission I’ll see they wake you early. Tomorrow being Friday, you’ll want to get all such business out of the way before things up here get even worse.”

She wrinkled her nose and said, “I wish you hadn’t reminded me. Are you certain there’s no way to get that hearing out of the way with a whole workday left before rigor mortis sets in?”

He grimaced and said, “I already tried. It’s no use. Even if we were closer to the county seat they’re more het up about that last train robbery and…”

“What train robbery?” she cut in. So he had to tell her the little he knew about that, too, and while he didn’t know that much, it was enough of a tale that they somehow wound up all the way inside with the hall door still ajar but the two of them sitting side by side on the bedstead. It felt mighty springy as well as cozy by the time he’d finished. But they both looked away, awkwardly, when it was obvious there was little more to say. So he said, “Well, I’d best get it on down the road so’s you can shuck and get some shut-eye.” But as he shifted his weight to rise, Willow put a soft hand firmly on his wrist to ask him, “Where were you planning on, ah, shucking for some shut-eye of your own, Stuart?”

He said, “For openers I have a new bedroll in the tack room out back. I’ll figure where to spread it once I find some grass not too many cows have just walked across.”

She pointed out, “The sky outside is already overcast and it’s not even midnight, yet. We’re in for some drizzle or at least heavy dew this side of sunrise.”

He repressed a yawn and replied, “I’ve woke up dew-dropped before. That’s how come I bought me a heavy duty canvas. If it rains outright I can always haul my bedding inside the stable or mayhaps under that planking over at the railroad stop. Fewer flies where no ponies are apt to be spending the night as well.”

She said, “Oh, for heaven’s sake, why don’t you just spend the night up here with me? You paid for the fool room, didn’t you?”

He nodded soberly and said, “There’s room on the rug for my new bedroll, but it would still be awkward. I didn’t bring along any pie-jamas, either, and despite our agreement I’m only human and can’t be held to what I might or might not try, half-asleep, on my way back from, ah, washing my hands in the wee small hours.”

She rose gracefully, kicked the door all the way shut, and flipped off the Edison switch before rejoining him in the sudden gloom to murmur, “I suppose I’ll just have to release you from that foolish promise, then.” So he started to say something clever in reply, saw nothing he could say was apt to please her half as much as what a man was supposed to do at such times, and reeled her in for a not at all platonic kiss in the dark.

She informed him silently just how platonic she was feeling, with her quietly questing tongue as they fell backwards across the bedding by mutual accord. But as his free hand roved up the inside of one of her knees to see what else she had to say to him so silently, he discovered just how tough it was to expose the privates of a lady in a split riding skirt to the elements. The infernal falsely feminine garment worked more like a pair of loose leather pants than anything a properly brought up young lady was supposed to wear lying down.

But she saved the situation by laughing shyly with her lips to his and murmuring, “Silly, let me undress myself if you don’t know how!” So he let her, taking advantage of her barely visible slithers in the darkness to get his own confining cloth and leather out of the way and anyone could see she’d been married a spell, and happily so, when she beat him to the buff by at least a minute and seemed to be all over him, naked as a jay, by the time he had his six-gun hanging handy over the bed post on his side.

Then he was in her insides and they were both experienced enough not to say anything that might sound overly anxious or uncaringly cool as they got to know one another in the Biblical sense, albeit hardly in a manner any established church might approve of. She didn’t bring that up before he’d brought her to climax, more than once and the last time on the rug with a pillow under the parts of her that might have otherwise been more bruised than his knees. But of course, being a properly broken-in young widow woman instead of a trailtown sport, she hugged him tightly to her with all four naked limbs to sort of sob, “Oh, that was lovely, dear heart. But what must you ever think of me now?”

He kissed her reassuringly and replied, “I think you do it better up in the bed, now that we’ve tried it down here, and we’d about agreed on how grim it figured to be stuck here at least four days and mayhaps more with nothing else to do.”

She stopped breathing under him for a few heartbeats and her voice dropped a tad in warmth as she answered, “Oh, is that what we’re doing in this odd position, killing time?” So he moved inside her a tad as he teased, “Well, you have to admit this has churning butter beat all hollow and i

f you don’t like this position we can no doubt find plenty of others to try between now and lord knows when.”

She laughed, informed him he was just awful, and asked if he’d think she was just awful if they tried it in the arm chair by the window with her on top.

Thus it came to pass that Monday morn seemed upon them before they knew it. For seventy-two hours in the company of a beautiful widow who’d been feeling mighty frustrated of late went surprisingly fast when she kept you in bed with her that much of the time.

By Monday morn they’d both been up and even out of the hotel just often enough to appear before the coroner’s jury over at the schoolhouse looking reasonably prim and proper. He’d shaved and put on a fresh shirt from his gladstone. Willow had bought a new summer frock after cashing that wired bank draft Friday morning and since this was the first chance she’d had to put it on, it was still store-bought fresh.

The hearing, after all the delicious delay it had caused at least two of those present, went cut and dried to the point of anticlimax. The county coroner from Auburn was too high on the political totem pole to appear himself. A deputy coroner who was as respected if not better known as a horse doctor presided over the panel of local merchants and cattlemen with nothing better to do. Willow was the only witness who’d actually seen the late Bad News Bradford throw down on Stringer’s spine, but they allowed her testimony would do. By this time the other mean things the renegade copper badge had pulled had caught up with him, clean up in the High Sierra, and they’d heard Stringer was all right. So what the hell.

The findings of the panel were Justifiable Manslaughter in Self-Defense with one cowhand holding out for Suicide after noting the simple facts that Stringer was a Sierra rider who wore a double-action slung sensible to draw natural. The deputy coroner said not to complicate things with nit picking and when Jethro Durler wistfully asked who might be entitled to any reward money on the late Wesley Bradford the old cuss with the gavel banged it and told him not to pick nits neither, adding, “Thanks to MacKail here, the wicked rascal was put out of business before he got important enough for a serious bounty. It is the officious ruling of Placer County that whereas no kith or kin have come forward to claim the remains and whereas the little the Postmaster General had posted on him for that job in Merced ought to just about cover the cost of his box and burial, I don’t want to talk about it no more and the case is closed.”

When Jethro objected in an injured tone that they’d planted that dead hobo that time for less than twenty bucks, hymns and roses thrown in, the deputy coroner insisted, “I just told you the case is closed. If you’re so anxious about reward money why don’t you go out after the rascals who stopped that train the other night? If it turns out they’re the Wild Bunch, like everyone says, you’ll be set for life once you catch only a few of „em, Jethro.”

Another panel member cackled, “By gum, I’d settle for the capture of just one of „em! Everyone in the Wild Bunch has so much bounty paper on him it’s a wonder any of „em can still git around! Aside from the state and federal rewards there’s the bounty posted by the Pinkertons and the personal promise of old Harriman of Western Union that he’ll fix up your whole family with lifelong railroad passes just for shooting Butch Cassidy’s dog!”

Stringer could see the hearing was starting to get interesting just as it was breaking up. He said, “Some say Butch and Sundance have left the country and, to tell the truth, I doubt any of „em could be this far west. But thanks to what you boys just put me through, no offense, I missed out on most of the details of that train robbery in Donner Pass. I take it none of the posses out after the rascals have cut any sign as yet?”

The older man who seemed to know so much replied, “ain’t but one posse still after „em. Marshal Lefors and his federal riders have been out after „em too long to give up just because the trail’s grown cold again. Lots of old boys from closer to here tore all over the higher country to the east right after the robbery. Didn’t find any sign on bare rock, of course. The robbers got away clean with over fifty grand in specie and Lord knows where they’re spending the same right now!”

Stringer whistled, started to ask a dumb question, and didn’t. He knew why that much hard currency had been on its way out to the coast when someone else grabbed it. Paper money was becoming acceptable to most folk in the states these days, but merchants and farmers used to Spanish cash in the Philippines weren’t about to sell food, fodder, or a daughter for anything but gold or silver they could test with their teeth.

He said, “Fifty thousand in specie carries sort of heavy, even if it was all gold coinage at twenty dollars to the ounce. I don’t suppose anyone’s considered scouting for a cache the robbers might be planning to come back for, later?”

By this time most of the others, including Willow, had drifted outside into the sunlight. The panel member he’d cornered looked wistfully at the open door and said, “I don’t know all that much about the infernal robbery and to tell the truth I’m sorry I even mentioned it. My old woman is waiting chicken and dumplings on me. So if you don’t mind…”

Stringer let him go and ambled after him, reaching for the makings and pausing on the schoolhouse steps to get his bearings and sort his thoughts as he rolled a smoke. Over by the water tower down the slope a train had just rolled into town. He regarded it with some wistfulness, knowing it would carry him down to civilization in about the time it was going to take him to explain his next best moves to good old Willow. He just had to make her face the fact that even if she wanted to put those riding duds back on he couldn’t take her with him over the pass and down into the Nevada Desert. For, aside from the way it would look to everyone else, he knew he had some serious riding ahead of him, now. The spunky roan he’d bought off old Diego figured to move faster than any cow, even walking. But Chuck Tarington and that foolishly-aimed market herd now had more than a three day lead on him and Rosalinda. Even as he stood there smoking, old Chuck and his boys would be pushing that hell-bound herd downhill and hence farther and faster than usual. Stringer had ridden the far slopes of the Sierra in his time and knew they were steeper as well as still fairly cool and shady on that side, until you got downslope a piece.

He started walking the way Willow had just gone, likely to take a ladylike leak at the hotel, from the length of the hearing and the way she’d lit out afterwards. He knew better than to rehearse future conversations in his own head, knowing they never turned out in real life the way you expected them to. He still found himself explaining to Willow about cattle drives, even knowing she had to know something about the subject herself, and that no matter what a man set out to explain to a woman, she was certain to spoil it all by asking some damned question he hadn’t expected her to.

By the time he got down to the tracks that train was pulling out to the west. He crossed over and stopped first at the closer Western Union to wire Sam Barca he’d been let off the hook by Placer County and that, yes, he was riding on after those dumb cows as soon as he tidied up a few last details here in Dutch Flat.

When he got back to the hotel he discovered he might have less to tidy up than he’d been dreading. When he went upstairs he found the door unlocked and the key neat and obvious on a pillow. He gave a soft holler anyway. The door to the ajoining bath was ajar and when he stepped in, neither the sink nor flush crapper looked as if they’d been used within the past few hours. So he used both and went on downstairs after locking up and pocketing the key. Willow had left no word at the desk, either. When he failed to find her anywhere on or about hotel property he decided, “Right. She saw her chance and grabbed for it.” Then he scowled and added, “Hold on. There wasn’t time for her to get back upstairs with that key, even if she saw no sensible reason to leave a note beside it on that pillow. She had it with her earlier, when we left for the schoolhouse together.”

He still wasn’t certain until he strode around to the alley between the hotel and the stable to open some trash barrels. When he found h

er split skirt in the second one, under her battered Stetson, he nodded down at them to murmur, “Well, adios and it was good to know you, querida. You were a hell of a lay as well as a mighty good sport about it in the end.”

Then he only had to stride through the back door of the stable, settle up and ride out. He’d already settled with the hotel by the day, in advance. A man who lived such an uncertain life just never knew when it would be time to ride on.

CHAPTER TWELVE

Considering its evil reputation, Donner Pass didn’t look all that ominous under an August sun and, in fairness to the illfated wagon party who’d made it so famous, Donner Pass was in fact as good a way as any to get over the spine of the Sierra Nevada. The mistake on the part of those poor pioneers of 1846 had been natural enough. They’d made her all the way cross-country to the far slopes of the Sierra without getting into too much trouble and it hadn’t started snowing when they’d headed on up the Truckee against the advice of the few mountain men they’d met up with along the way.

As Stringer rode Rosalinda the other way, with the railroad tracks pacing them up the gentle grade and a balmy breeze blowing gentle against his sun-warmed back, it was hard to picture ten feet or more of snow above the crown of his old gray hat and, in truth, there were whole winters where it hardly snowed enough up here to matter. The tracks over the pass were usually kept clear easily enough when the snow was normal. But he knew there were winters, such as the winter of 1846, when no snow plow or any other manmade object, including a man, was about to push through that much snow. The blizzard had hit the Donner Party after they were too high up the east slope to find any game to bring down, or to turn around and get back to the somewhat settled foothills before the food they’d brought along ran out.

Renegade 32

Renegade 32 Renegade 31

Renegade 31 Piccadilly Doubles 2

Piccadilly Doubles 2 Renegade 35

Renegade 35 Stringer and the Hangman's Rodeo

Stringer and the Hangman's Rodeo Renegade 28

Renegade 28 Renegade 23

Renegade 23 On Dead Man's Range

On Dead Man's Range Citadel of Death (A Captain Gringo Western Book 11)

Citadel of Death (A Captain Gringo Western Book 11) Renegade 33

Renegade 33 Over the Andes to Hell (A Captain Gringo Western Book 8)

Over the Andes to Hell (A Captain Gringo Western Book 8) Renegade 30

Renegade 30 Renegade 36

Renegade 36 Stringer in a Texas Shoot-Out

Stringer in a Texas Shoot-Out The Death Hunter

The Death Hunter Stringer and the Wild Bunch

Stringer and the Wild Bunch Renegade 29

Renegade 29 Renegade 21

Renegade 21 Stringer in Tombstone

Stringer in Tombstone Death in High Places (A Renegade Western Book 7)

Death in High Places (A Renegade Western Book 7) Macumba Killer

Macumba Killer Renegade 17

Renegade 17 Stringer on the Mojave

Stringer on the Mojave Blood Runner

Blood Runner Renegade 22

Renegade 22 Stringer and the Hanging Judge

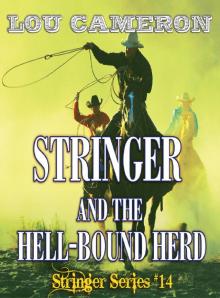

Stringer and the Hanging Judge Stringer and the Hell-Bound Herd

Stringer and the Hell-Bound Herd File on a Missing Redhead

File on a Missing Redhead Stringer on the Assassins' Trail

Stringer on the Assassins' Trail Mexican Marauder (A Captain Gringo Adventure #16)

Mexican Marauder (A Captain Gringo Adventure #16) Stringer

Stringer Renegade 19

Renegade 19 Stringer and the Oil Well Indians

Stringer and the Oil Well Indians Stringer and the Lost Tribe

Stringer and the Lost Tribe Piccadilly Doubles 1

Piccadilly Doubles 1 Stringer and the Border War

Stringer and the Border War Renegade

Renegade The Badlands Brigade (A Captain Gringo Adventure Book 12)

The Badlands Brigade (A Captain Gringo Adventure Book 12) Stringer and the Deadly Flood

Stringer and the Deadly Flood Renegade 25

Renegade 25 The Great Game (A Captain Gringo Western Book 10)

The Great Game (A Captain Gringo Western Book 10) Stringer on Pikes Peak

Stringer on Pikes Peak