- Home

- Lou Cameron

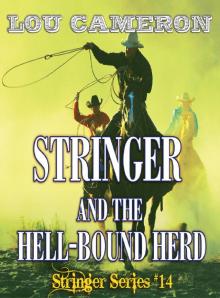

Stringer and the Hell-Bound Herd Page 2

Stringer and the Hell-Bound Herd Read online

Page 2

The cavernous interior was ablaze with Edison light despite the hour, and aclutter with the distracting Gibson Girls the infernal front office kept hiring every time they bought another typewriter.

Stringer strode on back to the frosted glass box they kept Sam Barca in, lest he make Gibson Girls faint with his pungent Paradi cigars and sulfuric swear words. Sam Barca was Stringer’s boss as well as the Sun’s senior feature editor. Anyone could see what being locked in a box behind a desk had done to a good reporter’s disposition. The crusty old fart had never offered a visitor a seat in living memory. So as Stringer approached, he grabbed an empty bentwood chair and dragged it on after him. He got to sit down, haul out the makings, and almost finish rolling a smoke before Sam Barca got around to glaring up at him instead of at all the papers on his cluttered desk.

Sam Barca was perhaps thirty years older and ten times uglier than Stringer unless one admired balding goat-faced Sicilians who favored green eyeshades and cigars that looked more like chaparral twigs charred by an August brushfire. Barca grimaced even worse as Stringer lit his Bull Durham and growled, “I don’t see what you get out of such mild tobacco. What happened? Did her husband come home at last?”

Stringer chuckled and replied, “I only wish I’d had that much fun. I’ve been following up on the killing of One Thumb Thurber down in Butcher Town, Sam.” To which Barca replied with a disgusted look, “For Chrissake, why? The item you turned in the day he was done in appeared on Page Nine, as you may recall. Have you any notion at all how many unimportant people get hit on the head every damned day in a city this size?”

Stringer thoughtfully blew a smoke ring before he declared, “The old gent was important enough to butcher before he could talk to me about something stinky in Butcher Town, Sam.”

Barca grimaced and said, “We don’t want to run anything about the way meat might or might not be packed down yonder along those mud flats, damn it. Another Scotch writer called Upton Sinclair keeps sending me unsolicited features on the meat-packing industry and I keep trying to convince him with hand-writ rejection slips that housewives don’t buy advertising space while meat packers do. But will any of you damned young Scotchmen listen?”

Stringer brightened and said, “I’ve read Sinclair’s stuff. He cranks out a heap of pot boilers for the pulp magazines. Didn’t know he’d started to publish exposés, though.”

Barca shrugged and answered, “He hasn’t. It’s one thing to write a piece on grinding the floor sweepings of a slaughterhouse into sausages and another thing entirely to get such garbage published! I told you when we ran your story on those purloined Texas cows turning up out our way that you were shaving it a mite thin, kid. I was able to save it for you with my trusty blue pencil, but as I told you at the time, there was no reason on earth for you to include all that shit about the way dead cows wind up so redistributed among all those industries great and small. Folk like to eat steak, light candles and fertilize their rose bushes. They don’t like to dwell on just where the products involved might have come from, via what route.”

Stringer said, “I doubt Thurber or anyone else down in Butcher Town noticed how untidy their chosen trade can get. Hosing down now and again would be safer and almost as easy as getting away with murder. I figure One Thumb’s tip involved something more scandalous than tainted meat or a little busted glass in the bully beef Uncle Sam’s been buying up so serious since the fighting broke out again in the Philippines. I thought I’d run over to Fort Mason this afternoon and see if either the Quartermaster or Transport officers had anything on old Thurber in their files. Detective Sergeant Gargan tells me the unions have been trying to get a foot in Uncle Sam’s Civil Service and half the warehousemen working at Fort Mason are civilians, these days, so…”

“Don’t you dammit dare!” Barca cut in, half rising from behind his desk as he elaborated, “I don’t want to hear about President Roosevelt being a good sport about your version of his charge up San Juan Hill. General William Shafter, the commander in chief in Cuba, has yet to forgive you for calling him a fat and lazy incompetent.”

Stringer looked pained and protested that the Colonel Shafter over at Fort Mason was no relation, as far as he knew. To which Barca replied with a snort, “Don’t bet on it. Nepotism got more than one Custer killed when I was covering Terry’s grand tour of the Black Hills. I’ve grown too old since then to look for another job. So consider yourself fired as of the split second you set foot-one inside Fort Mason and, hell, make that Fort Baker and The Presidio, as long as we’re on the subject of you getting anywhere near the military while you’re writing for this paper!”

Stringer blew smoke out both nostrils and muttered, “Swell. If you don’t want anything on that killing in Butcher Town or the fighting in the Philippines, could I interest you in a two-headed calf or the man eating artichoke of Madagascar? It’s that time of the year, Sam. School’s out, Congress has adjourned, and Bat Masterson writes way better baseball stories than me.”

Barca half growled and half soothed, “Now, you know I can always run one of your western-angle features, Stringer. Cowboy stories are a lot more popular since The Virginian came out than they were when I was covering the real thing in Dodge.”

Stringer scowled at the older man as he replied in an injured tone, “The trail dust I et working my way through Stanford was as real as any you ever tasted in the Long Branch Saloon, Buckaroo Barca. If you knew shit about the cattle industry you’d know how uninteresting it gets in High Summer. You’re not supposed to chase cows over hill and dale between roundups. They put on more beef if you just leave „em the hell alone on good range with halfway decent water handy.”

But Barca was only half listening as he pawed through the papers aboard his desk for something he must have thought more interesting. When he found the crumpled slip of foolscap he’d been looking for, he smoothed it with a triumphant cackle and declared, “A lot you know. I just got this news tip from an old drinking buddy in the press room of the Sacramento Bee. Ought to be worth a colorful Sunday feature, at least. Seems some big beef outfit’s amassing a herd over yonder with the avowed intent of driving „em to market the old-fashioned way. You figure you could milk eight columns out of such a nostalgic revival of your misspent youth?”

Stringer shook his head and replied, “Your old drinking buddy must have overdone it. I can see why he can’t sell the lead to his own paper. They still know what cowshit smells like, in and about Sacramento, and they’d stopped driving beef into Frisco on the hoof before I was big enough to herd chickens. The long drives of old were never intended as local color, Sam. They were the only way to get the damned beef to the nearest railhead so’s the fool cows could ride as much of the way as possible. I know how you feel about the Southern Pacific, Sam. But a cow could still ride cheaper, in a passenger coach, than you could ever herd it the same distance. Cowhands have to be paid, just like railroad crews, and it takes a full day to move a cow ten to twenty miles on its own fool hooves, so add it up.”

He saw that Barca was shaking his head, so he quickly added, “Even if some nostalgic asshole wanted to drive a herd in from Sacramento he couldn’t, Sam. Not without risking heavy railroad traffic highballing through his herd. The railroads follow the only right-of-way left. Everything else between here and Sacramento is cut up by irrigation ditches and bob wire. My kith and kin over in Calaveras County used to drive their market herds as far as Sacramento from the foothills to the east. I got to tag along a few times as a kid. Then they ran the tracks as far up into the hills as San Andreas and my Uncle Don commenced shipping his beef from there. Nobody drives a herd mile-one further than they have to, Sam. It may sound like fun, but it sure gets tedious.”

Barca grimaced and said, “I know the feeling. Trying to herd a word in edgeways can be a chore at times. I dammit never said they were planning on herding all that beef this way. They mean to push over the High Sierra by way of Donner Pass within the next few days. So if you got back in

your blue dungarees and hopped a train to Sacramento with a pad and pencil…”

“What would I write?” Stringer cut in, dryly, as he blew smoke out both nostrils. “Your pal on the Bee has to be joshing you, Sam. Nobody would be driving a California herd into the Great Basin in High Summer.”

Barca asked why. He was inclined to do things like that. So Stringer explained, “There’d be as much profit and no more work involved if you drove such a herd straight into Hell. You keep asking me to do features on the cattle industry, I keep telling you it’s an industry, not our own version of the English Fox Hunt or Spanish Bull Fight, and you keep crossing out anything I put in about profits and losses.”

Barca shrugged and said, “Our readers don’t care about reasons cowboys and Indians might or might not have for what they do. They just want to read about all the wild things they do, see?”

Stringer did. They’d had this discussion before. But he insisted, “Damn it, Sam, you’re not talking about Buffalo Bill shooting all those buffalo, free, because he couldn’t find any pop bottles to aim at. You’re talking about a Wild West yarn that’s just not about to happen because nobody in real life would ever act that wild.”

Barca frowned uncertainly but sounded firm as he demanded, “Why would my old pal on the Bee lie to me?” To which Stringer could only suggest, “One old-timer getting his facts wrong sounds a heap less loco than a whole cattle outfit indulging in cruelty to animals and bankruptcy at the same time. I reckon you could drive a herd over Donner Pass in High Summer, albeit I wouldn’t try it in the winter, and at any time of the year I’d as soon take the train. The Western Pacific runs cattle cars through there regularly.”

He snubbed the limp remains of his smoke out in a copper ashtray on Barca’s desk and continued, “Getting them down the far slope as far as Carson City or Reno wouldn’t be so bad, if it made a lick of sense. I fail to see how you could sell California beef as cheap as the Nevada beef grazing all along the Truckee, Carson, or Walker to begin with. I hate to be the one to tell you this, Sam, but raising beef is a competitive industry. Right about now Nevada stockmen ought to be busting a gut getting every head they can spare over the Sierra this way! Nobody is about to pay half as much as our own meat packers in Butcher Town, thanks to our Teddy’s anxiety to civilize the Philippines with plenty of Krag rifles and bully beef.”

Barca glanced down at the crumpled paper in his hand before he suggested, “Maybe that’s it. Says here the beef from Sacramento’s bound for a new mining town over by the Stillwater Range. Hard rock miners make three or more dollars a day, so they can afford steak and spuds most every night, and if the Nevada ranchers have already contracted to feed the army…”

Stringer laughed incredulously and cut him off with, “I liked it better when we were talking about grown men playing cowboys and Indians just for fun. Contracts are made to be broken when and if some damn fool miner’s woman wants to pay that much more for her beef than the U.S. Army!”

Barca asked how Stringer could be so sure of meat market prices in a distant desert mining town, so Stringer told him, “I don’t even know what they call the place or what they might be mining there. But it’s a matter of simple cowboy calculation, Sam. Can’t you see how dumb it would be to buy cows in California with the local price of beef sky high, then herd them, afoot, a good two hundred miles to compete with cheaper Nevada beef? Such a mythical trail drive would take a good two weeks, in kinder country and climate, Sam. Meanwhile a trainload of Nevada critters could get there, fatter, in no more than a few days.”

“Maybe there’s no way to get to that desert town by train,” Barca objected hopefully. So Stringer replied, “I just said that. From Reno east to, say, Fallon and the end of both water and civilization would take less than three hours by the slowest freight. To get a Nevada beef critter from Fallon to anywhere I can think of along the north-south Stillwater Range would cost you two to four days and no doubt a few pounds a head, following the water and summer-cured grass along the Carson River at least some of those days. Meanwhile, your mysterious hell-bound herd from Sacramento would be bawling dry and dusty across the sage and salt flats from where the Truckee swings away to the north around Fernley, three or four days west of the Stillwaters after an already mighty rugged drive over the Sierra. So add it up, Sam.”

Barca did, and decided, “When you’re right you’re right. I don’t know what could have gotten into old Andy Spinner. He’s usually pretty reliable. He must have gotten things wrong, like you said. The more I think back on the times I’ve had to cross the Nevada Desert in High Summer the easy way, aboard the U.P., the more I have to agree I’d as soon see a cow in Hell as out there on those sage and salt flats under an August sun. By the way, do cows eat sagebrush?”

Stringer smiled thinly and replied, “Get a cow hungry enough and it’ll eat the San Francisco Sun. But you’ll put more pounds on it with grain or good grass. Repeat the part about good grass, though. There’s a heap of confusion about so-called sage. The California black and white sages you trip over in the coast chaparral are really related to the herb garden sage some fancy cooks use. What we call sagebrush or just sage is more noticeable stuff related more to sunflowers than real sage. That’s how come it has yellow instead of pink or purple flowers.”

Barca groaned, “Jesus H. Christ, I ask him what time it is and he tells me how to fix a watch! All I asked was do cows eat sage of any damned kind or not!”

Stringer shrugged and answered, “Can’t say about herb garden sage. Sounds a mite spicy to graze in bulk, even if it grew that thick. As to Artemisia Tridentata or that gray green shit growing so thick in the Great Basin betwixt the Sierra and Rockies, I just told you cows could get it down if they had to. Sheep do better on it. But it takes the digestion of a pronghorn or jack rabbit to thrive on it. Do you want to know about cheat grass now?”

Barca laughed despite himself and said, “I covered that story when the pernicious weed first showed up out here, disguised as grass but made mostly of highly inflammable air. If you don’t consider that Sacramento story worth covering, where might you be fixing to head next?”

Stringer said lunch and Barca agreed that would be fine as long as he stayed the hell away from the military until they got through civilizing the Philippines. So Stringer got up, dragged the chair back where he’d found it, and that would have been that if one of their new Gibson Girls hadn’t cut him off with a sweet smile and a sealed letter, saying, “I don’t know why they keep putting mail addressed to you on my desk, Mister MacKail. But they do, so…”

“I don’t have my own desk, Miss, ah, MacTavish,” he cut in. It inspired her to pout prettily and reply, “The Auld Sasunnachs seem to think everyone whose name begins with a Mac must be related or, worse yet, Irish!”

He laughed and favored her with an “A mo mala!” or “Oh, me eyebrow!” as he took the letter meant for him. When he saw who it was from he was too polite to tell her his Uncle Don would doubtless have a fit if he knew a message in his own firm hand had passed through the hands of a MacTavish. She likely didn’t take those feuds in the old country as serious as he’d been taught in Calaveras County as a third generation Scot named after the big loser of “The „45.” It was hardly her fault her clan had fought on the winning side, and, damn, she sure had hot coals banked somewhere back there in her smoky gray eyes.

On the other hand, they both worked for the Sun and that artist’s model on the second landing of his boarding house glowed even hotter if a man wanted to mess around where he lived or worked. So he just thanked her, in English, since the Gaelic seemed beyond her, and lit out for lunch before his own fool eyes could get him in more trouble.

But a few minutes later he was back in Sam Barca’s cubbyhole, with the letter from home in one hand and a mighty puzzled smile on his face. Barca looked up to say, “That was quick. What did you eat for lunch, the smell from the kitchen?”

Stringer said, “I read this letter from the home spread as I was

waiting for a damned old menu. You knew my uncle, Don MacKail, runs a fair-sized herd on the M Bar K my grandfather started back in the gold rush days when he noticed more good grass than gold in them there hills?”

Barca looked pained and said, “Spare me your family saga unless we can run at least a column on the latest misadventures of the M Bar K Bunch. What kind of trouble have they gotten into now, both Joaquin Murrieta and that celebrated frog Mark Twain wrote about being long gone from Calaveras County, last I heard.”

Stringer said, “If I’ve told you once, I’ve told you twice they were both fictitious. Uncle Don says he’s been quoted a good price on some beef, better than he got this spring from the barons of Butcher Town. He’s asking me to check it out.”

Barca shrugged and asked, “What’s to check out? We were just talking about the price of beef going through the roof since Teddy whitewashed his Great White Fleet and found a spanking new tribe for the army to fight.”

Stringer shook his head and said, “That’s not all we were just talking about, Sam. Uncle Don says the only thing that sticks in his craw is the destination of some veal he was fixing to market as beef, come fall. He says he’s in business to make money, but he just can’t figure how some jasper called Tarington can hope to, running them guess where in High Summer?”

Barca smiled smugly and replied, “I don’t have to guess. C.J. Tarington is the cattle baron old Andy Spinner wrote to me about, earlier. The considerable amount of beef on the hoof he means to deliver is due in the mining camp of Wagon Springs, Nevada, before the end of this very month. So what do you mean to write your uncle, seeing you know so much more than old Andy Spinner about the cattle business?”

Renegade 32

Renegade 32 Renegade 31

Renegade 31 Piccadilly Doubles 2

Piccadilly Doubles 2 Renegade 35

Renegade 35 Stringer and the Hangman's Rodeo

Stringer and the Hangman's Rodeo Renegade 28

Renegade 28 Renegade 23

Renegade 23 On Dead Man's Range

On Dead Man's Range Citadel of Death (A Captain Gringo Western Book 11)

Citadel of Death (A Captain Gringo Western Book 11) Renegade 33

Renegade 33 Over the Andes to Hell (A Captain Gringo Western Book 8)

Over the Andes to Hell (A Captain Gringo Western Book 8) Renegade 30

Renegade 30 Renegade 36

Renegade 36 Stringer in a Texas Shoot-Out

Stringer in a Texas Shoot-Out The Death Hunter

The Death Hunter Stringer and the Wild Bunch

Stringer and the Wild Bunch Renegade 29

Renegade 29 Renegade 21

Renegade 21 Stringer in Tombstone

Stringer in Tombstone Death in High Places (A Renegade Western Book 7)

Death in High Places (A Renegade Western Book 7) Macumba Killer

Macumba Killer Renegade 17

Renegade 17 Stringer on the Mojave

Stringer on the Mojave Blood Runner

Blood Runner Renegade 22

Renegade 22 Stringer and the Hanging Judge

Stringer and the Hanging Judge Stringer and the Hell-Bound Herd

Stringer and the Hell-Bound Herd File on a Missing Redhead

File on a Missing Redhead Stringer on the Assassins' Trail

Stringer on the Assassins' Trail Mexican Marauder (A Captain Gringo Adventure #16)

Mexican Marauder (A Captain Gringo Adventure #16) Stringer

Stringer Renegade 19

Renegade 19 Stringer and the Oil Well Indians

Stringer and the Oil Well Indians Stringer and the Lost Tribe

Stringer and the Lost Tribe Piccadilly Doubles 1

Piccadilly Doubles 1 Stringer and the Border War

Stringer and the Border War Renegade

Renegade The Badlands Brigade (A Captain Gringo Adventure Book 12)

The Badlands Brigade (A Captain Gringo Adventure Book 12) Stringer and the Deadly Flood

Stringer and the Deadly Flood Renegade 25

Renegade 25 The Great Game (A Captain Gringo Western Book 10)

The Great Game (A Captain Gringo Western Book 10) Stringer on Pikes Peak

Stringer on Pikes Peak