- Home

- Lou Cameron

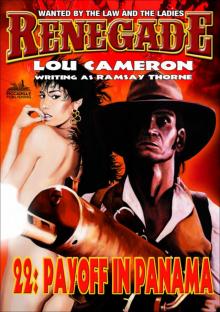

Renegade 36 Page 3

Renegade 36 Read online

Page 3

To reach the safety of the coastal swamp they had to cut. across the gunboat’s course at right angles, slowly. The gunboat was farther than the shoreline but moving a hell of a lot faster than the ketch. As Captain Gringo spotted the inlet Gaston had pointed out for him, he glanced back to see the gunboat, all of it, above the horizon and steaming at a good fifteen knots, with her gun turrets ominously tracking him!

He hoped they’d have the decency to fire a warning shot first. He might just make it if they’d only give him a few more fucking minutes. Gaston was yelling, “Faster, faster!’’ as if there was anything he could do about a tub that had never been built to chase anything faster than a red snapper. And then they had an outlying clump of mangrove between them and the gunboat and still it hadn’t fired.

Captain Gringo braced himself for some serious swimming, should he survive the blast. He knew that if the gunboat meant to fire, it would have to fire right about now. It couldn’t pursue them into the shallows, with its deeper draft. Sending a shore party up a creek after a vanishing ketch would be a drag compared to firing a salvo at it.

Gaston called down gleefully, “They are moving across our wake. Better yet, they just dipped their colors to us! They must be drunk.’’

“What colors are they showing?’’ Captain Gringo called back with a puzzled frown. Gaston shouted, “Imperial Spain,’’ and that explained it.

As Gaston slid down to join him, Captain Gringo steered on up the channel as the trees closed in around them and the trades began to lose their grip on the fluttering canvas above. He told the Frenchman, “They were just tracking us with their guns for practice. They must have taken us for a harmless fishing ketch. Spain’s already got enough to worry about without a war with Costa Rica.”

Gaston said, “True, mais in that case why are they steaming so hard so far south, with or without making the boom-boom?”

Captain Gringo shrugged and said, “They must be after bigger game. Since they’ve been putting those Marconi sets aboard the more important vessels, a gunboat skipper doesn’t have to see his prey to go after it. They’re probably after gunrunners. With things heating up in Cuba again, there must be a lot of that going on, right?’’

“Oui, I am so pleased to know we do not resemble any vessel that adorable Spaniard has on his list of shit. May I suggest we look out for arrows now? This is no ordinary tidal creek we have found, Dick. Anyone who knows this coast will have marked it down as a good place to put in for fresh water, and who knows this coast better than the Puna and Carib who lurk along it, hein?’’

Captain Gringo steered for the right bank of the creek as the winds failed them. They didn’t make it. The keel grounded a good ten feet from the grassy hammock between taller trees growing farther from the surf. Captain Gringo rose, moved forward, and stared down from the bow into water as dark and brown as tea, and about as easy to see bottom through. He muttered, “Shit, I’ll have to swim ashore with the painter. Maybe when the tide rises we can haul her in a little closer.’’

As he shucked his hat, jacket, boots, and gun rig, Gaston asked if he recalled how large some saltwater crocodiles grew in these parts. He put his wallet down atop his planter’s hat and picked up the end of the painter as he replied, “After that gunboat, what’s a little old croc? My asshole’s still puckered.”

Then he jumped overboard feet first and hit bottom with his bare heels just as his head went under. He only had to swim a few strokes before he could wade the rest of the way. He struggled up the muddy bank, crunched through the reedy grass to the nearest tree, and secured the line before he turned around and called, “Okay, just toss my gun ashore. It’s all I’ll need until we can rig a drier way to do this, Gaston.”

Gaston nodded, bent to pick up his gun rig, and swung it around like a bola before letting it fly his way.

His way wasn’t good enough. The chest strap caught on a low-hanging branch between ship and shore and the rig landed in the water between them, gun and all.

Captain Gringo swore and said, “Nice try. You and your own gun had best stay put for now. Maybe I can scout up some fallen balsa stalks for a raft.”

As he moved away from the water’s edge, Gaston bawled, “Mais non! Not without a gun, Dick!”

But Captain Gringo called back, “If I meet any bushmasters, I’ll stomp ’em barefoot. I’ve still got my pocket knife, and how big can this hammock be?”

It was bigger than it looked, he found, as he moved inland out of Gaston’s sight. He watched where he put his feet, despite his threat to the local flora and fauna. Snakes were seldom a problem this close to high noon if a guy watched where he was stepping. Jaguars and gators hunted mostly at night too. He was more interested in finding something that would float and was soft enough to work with his pocket knife. He spotted a clump of balsa and headed for it, reaching in his pocket for the knife. Then he froze in place as a very large human being with a very large ten-gauge shotgun, sawed-off, rose from a clump of sea grape to ask him reproachfully where the hell he thought he was going.

The big mestizo was dressed in the ragged dungarees and piratical striped shirt of a seaman, not a landlubbing peon. Captain Gringo said, “We just put in for fresh water, amigo. I am called Ricardo.”

The mestizo said, “First you will take your hand out of that pocket. Then we shall see if you are a friend or not. I am taking you to my skipper. I am not allowed for to decide such matters myself. Pero I do have permission for to blow the head off any hombre who does not come quietly, with no tricks.”

So Captain Gringo came quietly, with no tricks. He couldn’t think of any good ones with that formidable weapon trained on the small of his back.

The seaman herded him to the far side of the hammock, where another vessel, a bigger one, was anchored in another branch of the sluggish tidal creek complex. She was schooner rigged and painted black as a dead crow all over. Even her masts were the same flat black. Captain Gringo gasped hopefully when he spotted her familiar lines. But he told himself not to be silly. A gunrunner was a gunrunner. He couldn’t be getting that lucky all of a sudden.

But he was. When the crewman who’d captured him whistled, they lowered a jet-black longboat, and as it came ashore, he spied a familiar figure indeed in the bows. Esperanza spotted him at the same time. In the past Captain Gringo had filled her figure almost as much, she said, as her Junoesque figure filled the Basque shirt and white bell-bottoms she was filling to the breaking point. As her longboat grounded, the buxom Basque brunette leaped ashore, ran over, and bear-hugged him, gasping, “¡Oh, querido mio! How on earth did you ever find us?”

He kissed her as warmly as the grinning crewmen watching would allow and told her, “It wasn’t easy. I assume you just put in here because you spotted smoke above the horizon before we did?”

She said, “¡Es verdad! Is a Spanish naval blood-bucket we have been playing tag with for all of three days and nights. A girl in my line of work must know all the hiding places along this coast. You say they are after you too?”

He said, “Not really. We thought they were chasing us. They must have taken us for a fisherman putting into a Costa Rican village. Last I saw of them, they were moving south, poco tiempo.”

“Bueno, let us give them some time before we put out to sea again. I cannot believe meeting you, of all people, here of all places! Where is Gaston? Is he with you?”

“Where else? We just got run out of Costa Rica again. He’s on the far side of this hammock in a stinky old tub he’ll never miss. That’s if you’ll take us aboard your Nombre Nada, of course.”

She hugged him again and warned, “Try going aboard anyone else and I’ll have her heart out, querido mio! Come, let us go get Gaston.”

She turned and told her crewmen to stay where they were. They didn’t argue. Captain Gringo didn’t argue either when she dragged him into the first clump of wild bananas they came to in the middle of the hammock and proceeded to pull his pants down.

That part was

easy. Getting her out of her own shirt and bell-bottoms was harder, because she wore her duds tighter than he did. Esperanza lay back on their piled clothing with a hungry sigh and spread her pale, muscular thighs in welcome as he mounted her like the old pal she was. As he entered her, she bit her lower lip and hissed, “Oh, Maria y José, I keep forgetting how good it always is with you, you monster! Have you been true to me since the last time we did this?”

He started pumping hard as he assured her he’d been as true to her as she’d been to him. She laughed, wrapped her big legs around his naked waist, and proceeded to behave a bit like a monster herself. One of the things they’d agreed about in the past was that it was nice for a big strong person to screw another big strong person, because, for once, all concerned could let themselves go.

So they did, and the things they did to one another just about wrecked the wild banana grove and would have put many a smaller man and woman in the hospital, assuming they survived.

Esperanza was almost six feet tall and all muscle, albeit shaped a lot more like Venus de Milo than many a stevedore she’d whipped in many a fair fight. She was too professional a skipper to mess with her crew. So Captain Gringo believed her when she said she hadn’t had any for a while. He’d have believed her anyway, as she came so hard she almost twisted it off inside her and then begged for more. It was an easy enough request to grant her. The big Basque broad was beautiful as well as built. Her mysterious mountain race was pure white, as far as anyone knew about a people nobody knew too much about. But there was an odd cast to her features that seemed neither Latin, Nordic, Celtic, nor, hell, anything but whatever she was. He’d never met a Basque who wasn’t ugly as hell or very good-looking, and she was good-looking by Basque standards.

As he ejaculated in her a third time and went limp in her massive limbs, Esperanza hugged him all over and sighed, “Oh, let me get my breath back and I shall get on top, querido.’’

He chuckled fondly, kissed her, and said, “Let’s save it for later. By now Gaston must think I’ve been eaten by wild animals.’’

She said, “Grrr, let me eat you, my wild animal. You smell clean for such a hot day. How could you have known ahead of time I wished for to go down on you, eh?”

He laughed and said, “No kidding, he’s probably really worried and, ah, we will be sailing with you a ways, right?”

She let him go, and as he sat up to haul his pants back on, she said, “Sí, we are bound for Cuba with guns for Garcia. If we can get there alive. The Spanish have never patrolled this far from home port before and—”

“I wish you hadn’t said that,” he cut in, adding, “Okay, I guess it won’t hurt to stay aboard the Nombre Nadu with you. But don’t ask us to go ashore. We want no part of Garcia’s lost cause. I used to go in for lost causes, but I guess I must be getting old. Lately, I just don’t enjoy losing as much as I used to.”

She sat up, making him wonder why he’d been so hasty to put on his dumb pants as the sunlight dappled her lush breasts and ample curves. She reached for her shirt as she laughed and said, “Never fear, my toro. I do not intend to let you go ashore. I may not let you out of my cabin before I have had my wicked way with you and then had it some more—as wicked as it can get.”

Then she spoiled the view by slipping into her duds. Even dressed, nobody was ever likely to take her for a boy. He helped her up, and they walked hand in hand across the hammock to see Gaston sort of war-dancing on the bow of the ketch. He spotted them at the same time and called, “Now I know how you do it, Dick. You have this lamp you stole from an Arabian, and every time you rub it ... Shit me no shit, what is Esperanza doing here?”

Captain Gringo said, “Toss everything ashore and dog-paddle your skinny ass to join us. I think we’re going to Cuba after all.”

By five or so both Esperanza’s libido and the afternoon tide were ebbing. So La Nombre Nada put out to sea again. As Captain Gringo stood beside Esperanza near the helm, he could see that while the big brunette seemed the same as ever, in or out of bed, more than half her crew was new to him, and they sure were moving good for a sailing vessel with her black sails furled. When he commented on it to her, Esperanza explained her auxiliary screw was now powered by a spanking new internal combustion engine, provided by the same people she was running the guns for.

He knew better than to ask her just who that might be in front of a helmsman he didn’t know. The skipper of a gunrunner didn’t gossip with her crew much either, if she was smart. It was a lot harder to go into business for oneself when one knew only what one had to about the business. She could tell him later, if it was important. He already knew where the guns were going. So what the hell.

Gaston joined them, looking more worried than usual. He told the girl, “Forgive me, I was just having a look below without asking your permission. I did not think you wished to be disturbed, judging from the sounds I heard as I was about to knock upon your species of door.”

Esperanza blushed and told him he was free to assume he had the run of the ship, aside from her stateroom when the door was shut, of course. Gaston nodded and said, “Eh bien, I assumed as much. Your cargo seems securely stored. I did not open any of the crates marked farm machinery. One hopes the ammunition is stored under the hopefully empty guns, of course?”

Esperanza nodded and said, “I have carried high explosives before, Gaston. I always have it as close to the bilge as possible, with as much metal as I can manage between it and a lucky shell.”

Gaston nodded and said, “I assumed the heavier boxes marked as seed grain were the ammo. Mais why do you have fuel tanks for a naphtha-burning engine aft, under this very poop, my child?”

Esperanza frowned and said, “That’s where they installed the tanks for me, Gaston. They’re handy to the engine room, mounted above and behind like that.”

Gaston looked at Captain Gringo, sighed, and asked, “Do you wish to tell her or shall I?”

Captain Gringo shrugged and said, “There’s not much we can do about it at this late date.” He saw Esperanza was sincerely puzzled and told her, “Naphtha can be as explosive as gun cotton, even when nobody is lobbing shells into it during a stern chase. One lucky round or, hell, one nasty accident with static electricity would take out your stern, your helm, and anybody standing right where we are about now!”

She looked concerned, but she, too, said, “It’s too late to do anything about it, querido. We would need shipyard facilities to dismantle Nombre Nada and put her back together another way. Once I deliver this cargo and have the time, I may do so, however. Where would you put the fuel tanks if it was up to you, querido?”

He said, “Below your waterline, between the engine room and main hold. You must have more room in your hold now with the old boilers gone, right?”

She nodded and said, “Si, and on this trip it is still not enough. We carry enough for to arm a battalion, querido. Krag and Springfield rifles, half a dozen machine guns, at least ten tons of thirty-thirty rounds for to go with them, and even some medical supplies.”

Captain Gringo grimaced and said, “It’s always nice to have some iodine on hand when you issue that many weapons to green troops. How the hell are we supposed to unload that big a shipment if and when we get there, Esperanza? You don’t have more than a dozen in your crew, do you?”

She said, “We are sailors, not stevedores. Garcia’s people will unlade and pack the supplies to him. We do not even have to go ashore.”

Gaston said, “Bless you, my child. That is the sweetest thing you have ever said to me.”

Then the lookout posted in the rigging above them said, or rather yelled, something that did not sound sweet at all. Everyone but the helmsman turned to stare south at a dirty sepia smudge against the darkening sky. Esperanza swore in Spanish and threw in some Basque that sounded even dirtier before she announced, “It’s that Spanish gunboat again, curdle his mother’s milk! Make for the shore, José. It is almost dark, and—”

“Belay that!�

� Captain Gringo cut in, explaining, “I know it’s your ship, sweet stuff, but if there’s one place you don’t want to be at sunset it’s against the sunset, outlined by the same!”

The helmsman had already swung the helm hard over. Nobody had told him the strange Anglo was the skipper of La Nombre Nada. But Esperanza said, “You heard my mate, helmsman. Is true we cannot make the shallows before they overtake us and is dark and getting darker to the east!”

José shrugged and spun the wheel the other way. As they put about directly into the wind, Esperanza asked the world in general, “For why did that gunboat turn around? It was chasing us south along the coast when we eluded it. It did not see us putting in or it would not have steamed on, no?” Gaston suggested, “Perhaps it is another gunboat, or not a gunboat at all, hein? We are, after all, in a well-traveled sea lane.”

Esperanza shook her head and said, “It is moving much too fast for a cargo vessel. At the same time it is burning soft coal. Nobody but the Spanish Navy bums anything but oil or anthracite these days. The Dons still think they own the sea, so they do not worry about who may see them at a distance.”

Gaston sniffed and suggested, “Perhaps they burn cheap fuel after billing the palace for something more expensive. Such things happen when the King is a ten-year-old boy and his regent is an unpopular Austrian widow who barely speaks Spanish.”

Captain Gringo swore and said, “Never mind why they’re burning soft coal. They’re still moving pretty good. Are we at full speed, Esperanza?”

She nodded and said, “Sí. I never use my engine unless I am in a hurry. Oh, damn, I can make out her masthead now! That means they have us spotted too, no?”

“Yeah, and they were on course our way to begin with. Do you have anything heavier than a machine gun below, doll?”

She shook her head but suggested, “Perhaps if you manned one of the Maxims, mounted here in the stern?”

Renegade 32

Renegade 32 Renegade 31

Renegade 31 Piccadilly Doubles 2

Piccadilly Doubles 2 Renegade 35

Renegade 35 Stringer and the Hangman's Rodeo

Stringer and the Hangman's Rodeo Renegade 28

Renegade 28 Renegade 23

Renegade 23 On Dead Man's Range

On Dead Man's Range Citadel of Death (A Captain Gringo Western Book 11)

Citadel of Death (A Captain Gringo Western Book 11) Renegade 33

Renegade 33 Over the Andes to Hell (A Captain Gringo Western Book 8)

Over the Andes to Hell (A Captain Gringo Western Book 8) Renegade 30

Renegade 30 Renegade 36

Renegade 36 Stringer in a Texas Shoot-Out

Stringer in a Texas Shoot-Out The Death Hunter

The Death Hunter Stringer and the Wild Bunch

Stringer and the Wild Bunch Renegade 29

Renegade 29 Renegade 21

Renegade 21 Stringer in Tombstone

Stringer in Tombstone Death in High Places (A Renegade Western Book 7)

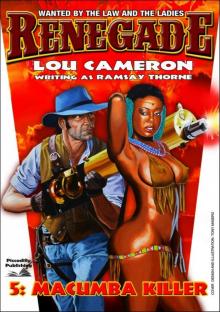

Death in High Places (A Renegade Western Book 7) Macumba Killer

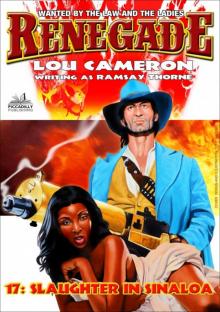

Macumba Killer Renegade 17

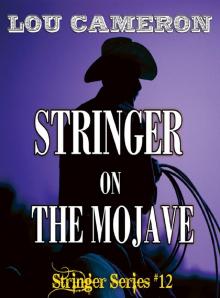

Renegade 17 Stringer on the Mojave

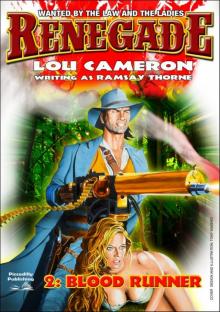

Stringer on the Mojave Blood Runner

Blood Runner Renegade 22

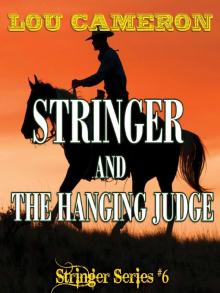

Renegade 22 Stringer and the Hanging Judge

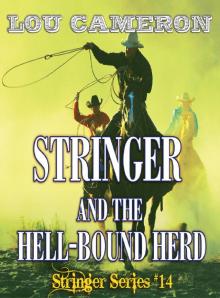

Stringer and the Hanging Judge Stringer and the Hell-Bound Herd

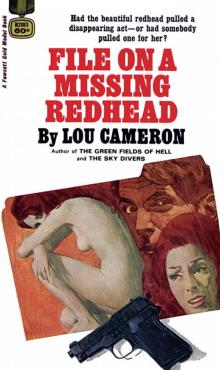

Stringer and the Hell-Bound Herd File on a Missing Redhead

File on a Missing Redhead Stringer on the Assassins' Trail

Stringer on the Assassins' Trail Mexican Marauder (A Captain Gringo Adventure #16)

Mexican Marauder (A Captain Gringo Adventure #16) Stringer

Stringer Renegade 19

Renegade 19 Stringer and the Oil Well Indians

Stringer and the Oil Well Indians Stringer and the Lost Tribe

Stringer and the Lost Tribe Piccadilly Doubles 1

Piccadilly Doubles 1 Stringer and the Border War

Stringer and the Border War Renegade

Renegade The Badlands Brigade (A Captain Gringo Adventure Book 12)

The Badlands Brigade (A Captain Gringo Adventure Book 12) Stringer and the Deadly Flood

Stringer and the Deadly Flood Renegade 25

Renegade 25 The Great Game (A Captain Gringo Western Book 10)

The Great Game (A Captain Gringo Western Book 10) Stringer on Pikes Peak

Stringer on Pikes Peak